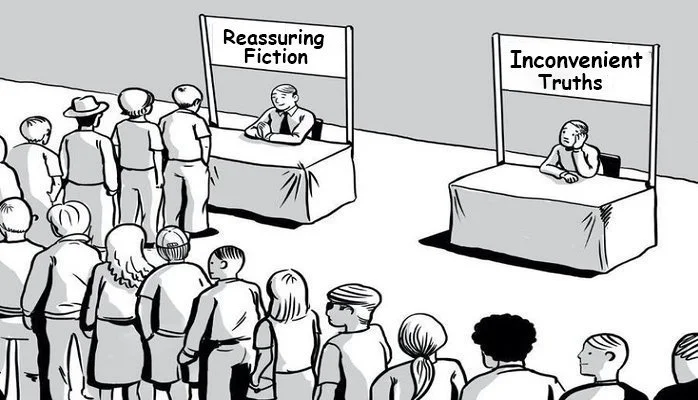

Every now and then a new concept spreads like wildfire and is soon adopted at scale by organisations and professionals within a given domain. This is a scenario that seems to be especially prevalent within professional sport and the performance sciences in general. Initially early adopters are drawn in by an appealing message and a story that they find compelling. As the idea gathers steam, the growing uptake seems as much motivated by anxiety and the sense that ‘everybody else seems to be into this, so perhaps I should be too’. In due course the concept becomes firmly established and its legitimacy is widely accepted. For those caught up by this wave (or mown down by it) this all seems to occur with dizzying speed. All of this speaks to the captivating effects of ideas and the power of narratives. It also begs the question how might we avoid being taken captive and resist being swept up by the tide. Even once the wave has subsided, these events leave in their wake a detritus of zombie ideas that we as leaders, coaches and practitioners must navigate thereafter.

Figuring It Out

Leaders, coaches and practitioners who aspire to excellence typically recognise the imperative for life-long learning. Given the diversity and complexity we encounter when working with humans there is an ongoing need to assimilate new information. Within a professional context as with other aspects of our lives we figure out how the world works through inquiry and sense-making. It all begins with a question. Young children ask questions constantly as they strive to discover more about the world around them and how things work. They then proceed to make sense of things and this is based not just on what answers they were given but also their own experiences and ongoing explorations as they move through the world. What is striking is how much of this is done independently. As grown ups we can learn much from this approach. If we wish see the world as it is and to figure out how things operate in reality it follows we must enlist the same tools of inquiry and sense-making.

Questions on Talent Development

What are the key principles of youth athlete development and how do we best structure this?

Beyond the disputes on the specifics of the LTAD model, I think the term ‘Long-Term Athlete Development’ describes each of the most salient principles.

So the first principle is thinking long-term. To give the example of a national development programme, we should not be unduly concerned about winning junior-level competitions. Our approach should rather reflect the ultimate mission, which is to produce athletes who are capable of winning on the world stage as a senior.

It’s Lonely at the Top: Enlisting Support for the Leader

When individuals ascend to the top of the coaching tree or high performance structure they are faced with a host of new challenges that are beyond and often quite different to anything they have encountered in their professional career previously. At the time of being appointed into head coach, performance director, athletic director or general manager positions it is very rare that the individual is fully equipped for the range and scope of the challenges they will face. Beyond the question of how might we better prepare individuals for such pivotal roles, a more pressing question is what specific provision is available for those who find themselves in these positions.

Achieving Engagement and Alignment

As the march to high performance systems continues we have yet to resolve how to unite all parties to the cause. The estrangement between sports science (and medicine) and those operating in the field has proven to be a recalcitrant problem. Just as there is an ongoing divide between academic research and applied practice, achieving alignment between support staff in different disciplines and the coaching staff (not to mention the athlete as the ‘end user’) often proves to be elusive. Proponents of sports science and medicine often rail at how coaches and athletes seem reticent to adopt new findings and assimilate evidence-based practice, despite the merits presented in the research literature. Support providers commonly bemoan a lack of ‘buy in’ from the coaching staff, whereas researchers similarly cite a lack of compliance from athletes and coaches as thwarting their attempts to take interventions from the lab into the field. Here we will attempt to unravel these issues and explore some solutions to bring the respective parties together in our quest to unite the holy trinity of coach, support staff and researcher scientist.

Judging What to Prioritise and When for a Young Performer

Getting a handle on a young performer’s present status from a developmental perspective is crucial. After all, without this information we have no real frame of reference for making judgements or deciding on the best way forward. The reason that talent identification policy and development pathways at junior level frequently go awry in practice (as we noted in a previous post) is in large part due to a failure to account for maturation and relative age effects. Young performers at age-grade level are far from a homogenous group. Kids in the same age group may be at very different points in their trajectory. That growth and development curves for young performers can vary so widely inevitably thwarts any attempt to adopt a blanket approach. Whilst individual growth curves eventually converge, during their formative teenage years young performers can differ dramatically in how they present at any given time and this is manifested both physically and in the performance capabilities that they exhibit. Given that much of the variability we see at age-grade is simply due to the fact that kids are at very different stages in their relative stage of development, it follows we need some way to assess where a young performer is on their individual growth trajectory. Aside from the addressing the challenge of parsing genuine ‘talent’ versus maturation effects for sporting organisations, we equally need to be able to evaluate these factors on an individual level to inform decisions on how to best support the young performer. In this post we present a tool to estimate biological age and relative stage of maturation and describe how to use this information to inform the priority areas for development and guide training for the young performer.

Developing True Expertise

The online world and social media in particular is overrun with self-proclaimed experts - we might call them virtual experts. But as with truth, real expertise is as rare as ever in the digital era (notwithstanding the aforementioned ‘instant expert’ social media phenomenon). One reason why true experts remain such a rare breed is that developing expertise is a complex and multifaceted process that takes many years and arguably is never complete. Even with unprecedented access to information, acquiring expertise is arguably no more straightforward, encompassing as it does not only the acquisition of theoretical understanding but also applied knowledge and practical skills across multiple areas. Most coaches and practitioners aspire to attaining real expertise and as most will testify this journey and the real learning begins only once we leave formal education and enter the profession. This distinction between education and learning is an important one when seeking to develop expertise, as we will explore. It is similarly crucial that we understand the true purpose of teaching and the role of teachers, master coaches and mentors in guiding the process. Finding enlightenment and the pursuit of mastery however remains the domain of the individual and it is as much a process of self-discovery as anything else. There are also a number of steps and various stages to this journey.

How to Evolve Faster than the Opposition

Sport never stands still. Whatever our context or chosen discipline, what constitutes a winning strategy is continually evolving. Trends emerge and endure through a process of natural selection. Conventions in coaching and the prevailing wisdom on ‘best practice’ similarly morph over time, albeit other influences are also often at play. Remaining at the cutting edge relies upon our ability to adapt faster than the opposition. Within our environment the challenge is to evolve what we do and how we do it to preserve a competitive advantage. Being attuned and responsive to the constantly shifting dynamics also allows us to adapt to new challenges, respond to emerging threats from rivals and accommodate unforeseen events that change the rules of the game.

Lessons from 2020: Emergence of the Autonomous Athlete

The initiative and intrinsic motivation to train solo successfully for extended periods are rare and vital qualities for any aspiring performer. Over recent months the lack of direct coaching supervision, restricted access to training facilities and absence of training partners posed huge challenges for athletes at all levels, testing not only their will but also their ability to find a way. Regular readers will recognise that these are not new themes - as noted before the biggest test of a coach is what happens when we’re not present. With the unprecedented events of 2020 all of this very much came to the fore. The critical role of agency and the need to ensure that athletes are capable of functioning independently are arguably among the biggest lessons that coaches, practitioners and indeed the athletes themselves can take from this tumultuous period.

What You See Is Not All There Is

To explain the title, one of the most common cognitive biases in how we see the world is encapsulated as ‘what you see is all there is’. In other words, we have a tendency to overlook what is not immediately visible or obvious. We tend to assume that what we see in full view constitutes the only aspects at play. We are slow to consider that there might be additional unseen factors at work that might lead us to an alternative explanation for what we are seeing. In most circumstances we are dealing with incomplete information and there is always some degree of uncertainty and ambiguity involved in human performance. These are not bugs in the system that must be fixed, but rather features that we need to learn to navigate.