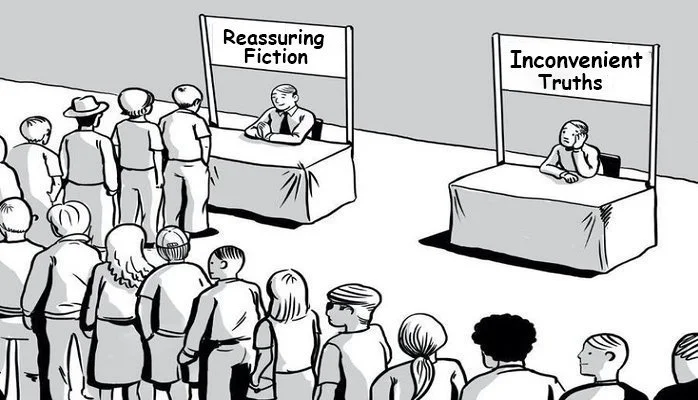

Tempering is a process used to impart strength and toughness, and essentially serves to bring out the intrinsic properties of the material under stress. Athletes forged in the crucible of severely testing conditions may be similarly rendered highly resilient to future challenges and stressors. Those who successfully come through such trial by fire paradoxically often prove stronger from the experience. The notion that stressors can not only make systems more resilient, but in fact stronger and better as a consequence, speaks to the concept of antifragility, a phenomenon observed in nature and highlighted by Nassim Taleb who famously coined the term. In this post, we will bring this antifragility lens, and a general reticence to accept that sports injuries ‘just happen’, to reframe how we think about preparing athletes to ‘future proof’ them to risks and scenarios that we cannot fully anticipate. In place of safeguarding measures and interventions that seek to protect, we will make the argument for tempering athletes to harness and develop their intrinsic reserves and coping abilities. Adopting this perspective and general strategy for managing injury risk, we will outline some tactics to help guide practitioners in their approach.

Emotional Aptitude in Athlete Preparation

Emotion has traditionally been viewed as something to be suppressed. The logic goes that as leaders and people in positions of authority we should be detached and act ‘without emotion’. If somebody is described as ‘emotional’ generally this is construed as a bad thing; when we become ‘emotional’ the implication is that we are no longer being rational or we are not capable of reason. Conventional wisdom advocates we avoid an emotional response or making emotional decisions. In contrast to these established views, more recent study in this area demonstrates that emotion is in fact integral to reasoning, decision making, guiding our behaviour, and our ability to relate to others. Emotional intelligence is accordingly becoming recognised as being at least as important as more established forms of intelligence. Indeed we increasingly hear commentators proclaim that ‘EQ trumps IQ’. In this latest Informed Blog we delve into the role of emotion in coaching and our work with athletes, and explore what aptitudes we need to possess in this area as leaders, coaches, and practitioners.

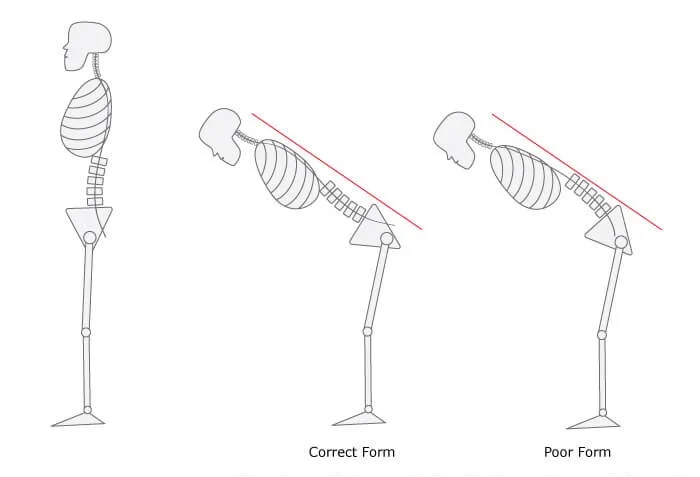

Informed Shorts: Is 'Hip Hinge' Really a Fundamental Movement?

The Why, What, and How of Coaching Movement: Part 1

In an early post entitled ‘The Rise of the Movement Specialist’ we identified an apparent gap in the technical input and direction provided to athletes when it comes to athletic movement skills. The appearance in recent times of hordes of self-styled ‘movement specialists’ seeking to fill the void, or rather recognising a niche in the market, is indicative that something is presently lacking. With this 3-part post we attempt to tackle the question of what our role is in this space, and offer some guidance on how we can do better.

In this first part of the 3-part series, we start with ‘why’…

Nuance - The Path to Enlightenment in Athletic Preparation

Nuance is an under recognised keystone of practice in elite sport. We have spoken previously about critical thinking as a critical skill for coaches and practitioners in the Information Age, as a means to evaluate and integrate information from different sources. Nuanced understanding is critical for the steps that follow. Nuance is required to derive real meaning from the knowledge acquired and make use of it. Nuance is also critical to cope with the complexity inherent in human performance. In this post we will make the case for practicing nuance as an active skill in order to combat the epidemics of superficial knowledge and binary thinking.

A 'Meta-Learning' Approach for More Productive Training

Athletes and coaches across all sports incessantly speak about the importance of 'focussing on the process', and process goals. As coaches and practitioners we are likewise ever mindful of scheduling constraints and the need to make best use of the finite time permitted to prepare our athletes. In previous posts we have spoken about the importance of mobilising mental resources, and the critical role of athletes' perception in relation to training responses. Here we will venture into the realms of teaching and learning, in order to make meaningful use of the notion of 'process focus' in the context of sport. In our quest for more purposeful training we will explore the concept of 'meta-learning', and outline how these principles might be applied to the process and the practice of preparing athletes.

Unravelling 'Locus of Focus' - Where to Direct Athletes' Attention When Training and Competing

Locus refers to a place or position where something is located: locus of attention concerns the location of an athlete's focus when executing a movement. Typically, locus of attention is stratified into internally versus externally located focus. The current dominant message to coaches and practitioners is to cue in a way that avoids an internal focus of attention - essentially 'internal focus BAD; external focus GOOD'. Yet when we look beyond the dominant narrative and take a closer look at the research on the topic, the question of where and how to direct an athlete's locus of attention when learning and performing becomes rather more complex. There is growing evidence to indicate that what is optimal may vary according to the population concerned, the task, context and even individual preference or predisposition. In this post we will delve deeper and attempt to unravel the topic of locus of focus.

The Burden of Advantage in Athlete Development

The paradoxical burden of advantages is something that those who work with young athletes (and young people in general) often grapple with. We might consider this a 'first world problem of privilege' for developing athletes; some might even argue it is symptomatic of the wider ills of modern society. Whether or not you subscribe to such views, few would disagree that a sense of entitlement is the enemy when developing young people, regardless of whether the aim is that they grow up to become good people or top athletes. In either scenario, many of the qualities we are seeking to instill are much the same.

As we will explore in this post, the luxury of advantages, unless carefully managed, can pose a serious problem when our aim is fostering the traits necessary to strive for mastery and achieve long-term success in sport. We will investigate what makes a conducive environment for developing young athletes who demonstrate 'talent', and what pitfalls to avoid. Finally, we will tackle the question of how we might negotiate the challenges we presently face on our quest, and recommend practical steps to ensure young athletes are equipped with the fuel for the journey and the tools to overcome obstacles on the path to becoming elite.

Perils of the 'Talent' Label

Athletic talent and sporting potential are hard to define and harder still to capture. Such ambiguity presents a major challenge for 'talent identification' and 'talent development' programmes in sport. Marking out a youngster as 'talented' is not only fraught with uncertainty, doing so can also carry negative consequences for their development moving forward. In this post we will explore the topic of 'talent' and discuss the challenges inherent in the processes of talent identification and development. In light of these issues we will examine how we might best nurture and develop young athletes whilst avoiding the pitfalls that can result from labeling them as 'talented'.

A Practical Take on Long-Term Athlete Development

'Long-term athlete development' has perhaps never been more topical, with an ever-growing number of programmes worldwide providing training for children and adolescent athletes. Mostly there is agreement on the need for structured 'athlete development' programmes for kids who engage in youth sports. We have consensus that appropriate physical and athletic development is beneficial for kids' health, performance and long-term outcomes. Still, confusion remains among parents, young athletes and practitioners, as authorities in the field continue to hotly debate the details. Here we will attempt to cut through these debates and provide much needed clarity and context to resolve some of the confusion. As we generally agree on the 'why', we will attempt to move things forward by finding shared ground and common principles to guide the 'what' and 'how' in relation to long-term athlete development.