In elite and professional sports there is obvious incentive to ensure athletes make a prompt and successful return to action following injury. There is a clear impetus to push the envelope in an attempt to accelerate the recovery process and minimise the time spent on the sidelines. The impressive recovery times reported with common injuries in professional sports are testimony to the success of the progressive and innovative approaches presently employed. In a ‘high performance’ setting athletes benefit from having a staff of professionals at their disposal on a daily basis to support the endeavour. Given such dedicated support it is perhaps unsurprising that athletes at the top level also show a far higher likelihood of making a successful return to their preinjury level following severe injuries such as ACL rupture, compared to what is reported with performers at lower levels of competition. The stakes involved might differ below the elite level but there are nevertheless lessons to be learned from their approach to performance rehabilitation and return to competition. In this latest offering we explore the advances in how we deal with sports injuries and consider what lessons we might adopt to improve outcomes for performers at all levels.

The Olympic Pursuit of Inspiration

For the most part, when those in the media talk of 'inspiration' or 'being inspired' they are referring to those watching sport being inspired to strive to achieve the feats that they have seen or attempt to emulate sporting heroes. In this way, great athletes are often described as 'an inspiration to others'. Essentially, this is inspiration borne of admiration - essentially the 'I want to be like them when I grow up' scenario.

The alternative meaning of inspiration - and the definition that this post will mostly focus on - is inspiration in the sense of stimulating thought or inspiring new ideas.

Solving the Puzzle of Training Young Athletes

A famous and often cited quote in relation to training youth is that 'children are not mini adults'. Clearly the approach to physical preparation for children and adolescents should differ to what is employed with athletes competing at senior level. This is evident from biological, physiological and long term development perspectives. What is less clearly defined are the specifics of how our approach should differ, and how this will alter according to the respective phase of growth and maturation. In this post we will aim to shed some light on this topic.

The Simplicity and Complexity Paradox in Training and Coaching

In a presentation last year I used the concept of yin and yang to describe the inter-relationship between physical and technical in track and field athletics. In essence, yin and yang describes how opposing elements (light and dark, fire and water) paradoxically serve to complement and ultimately define each other. Much the same applies when considering simplicity versus complexity. There are many instances where each of these elements apply in the realms of coaching and various facets of practice in elite sport. In this post we will explore the paradoxical - or yin and yang - relationship between simplicity versus complexity in the fields of coaching, physical preparation and sports injury.

Accountability - The Holy Grail for 'High Performance' Systems

High performance has become a buzz word that appears constantly in relation to sporting bodies and organisations associated with sports worldwide. The reason for the inverted commas 'High Performance' in the title is that this term has become so over-used and misused that it has arguably been rendered meaningless. Using the label does not make it so. In this post we discuss the elements that must be present in order for an environment and the practitioners who work in it to merit the title 'high performance'.

Lessons Along the Way - Advice for Young Practitioners

Providing learning opportunities and mentoring to coaches and practitioners has been a recurring theme throughout my career. Indeed a large part of my present role involves mentoring young coaches and practitioners in the early stages of their career working with athletes. These interactions frequently prompt me to reflect on my own journey and what I have learned on the way. This post is a collection of those critical lessons - essentially what would have been useful to have been told starting out.

'You Must Have Good Tyres' - Why and How to Train the Foot

Aside from serving as the point of weight-bearing for all activities performed in standing, the foot represents the terminal link in the kinetic chain where forces generated by the athlete are transmitted to the ground beneath them. The action of the foot is integral to all modes of gait, from walking to sprinting. During sprinting, for example, the athlete's technical proficiency in how they apply force during each foot contact is recognised as paramount. Despite the integral role of the foot in locomotion and a host of athletic activities common to the majority of sports, training to develop this critical link is often overlooked in the physical preparation undertaken by athletes. This post examines the role of the different muscle groups involved in the dynamic function of the foot. We will explore different training modalities to develop the respective muscle groups, and also discuss the applications of this form of training, from both sports injury and performance perspectives.

Yin and Yang of Physical and Technical

During my recent trip to AltisWorld I was invited to present to the coaches and practitioners attending the 5-day coaching clinic known as the Apprentice Coach Programme. My chosen topic was the interaction and relationship between the physical preparation undertaken with athletes (in this case track and field) and their technical development. The message I sought to convey was that the elements of physical and technical are so inter-related and dependent upon each other as to be inseparable; this brought to mind the notion of Yin and Yang.

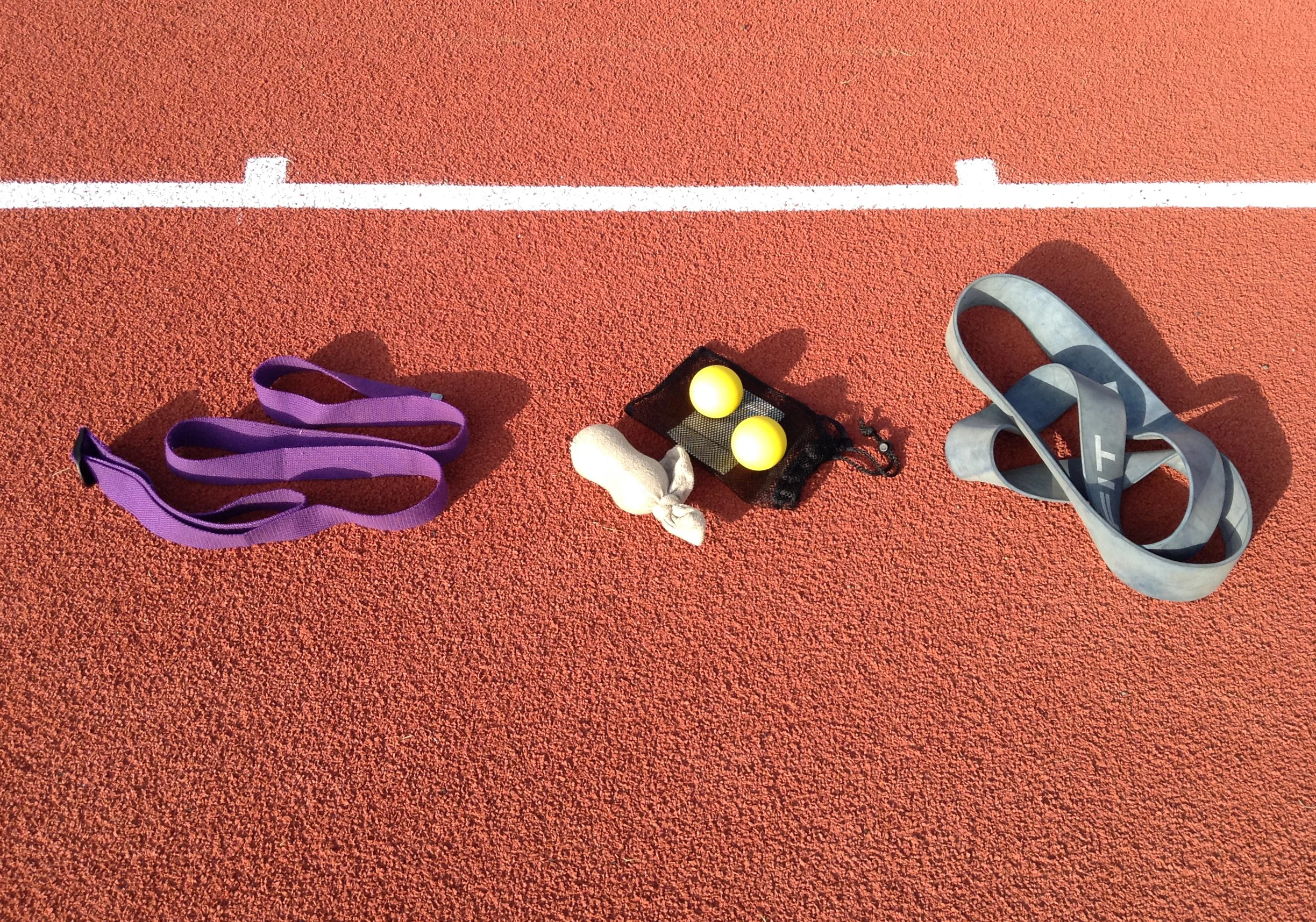

Self-Therapy Tools Part Two: What, When and How...

More enlightened training environments (notably AltisWorld) are throwing light on the benefits of ready access to performance therapy on a daily basis at the training facility. Whilst a growing audience is taking note, the reality for the majority of athletes is that they remain in less evolved systems and training environments that lack this provision. For the unfortunate majority self-therapy tools offer a substitute to hands-on manual therapy. In part one of this post we made the selection of what self-therapy tools merit the precious space in an athlete's kit bag. In this follow-up post we will now discuss the what, when and how.

Self-Therapy Tools for the Athlete's Kit Bag

I read with interest a recent article entitled 'Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Please do not use a foam roller!' from esteemed sports physician Andrew Franklyn-Miller. I moved away from using foam rolling some years ago, so it was interesting to see this. There is some data to support the efficacy of self massage using a foam roller to improve range of motion and other functional measures. However, by its nature the foam roller is a blunt tool. Applying compression over such a large area, the foam roller is too imprecise to be useful for self-myofascial release via trigger point therapy. Morever, excessive and non-selective use of foam rolling has the potential to cause more trauma to the tissues than good. This discussion also prompted the topic of this two-part post - if not the foam roller, which of the growing array of self-therapy and recovery tools on the market is worth the investment and space in the athlete's kit bag? In part two, we will explore in more detail how to best use those tools that make the cut, with some examples.