Whatever the nature of the sport, the coaching structure and system of athlete support, a full 360 degrees of mutual understanding should ultimately be the goal for all parties involved (athlete, coach, practitioner).

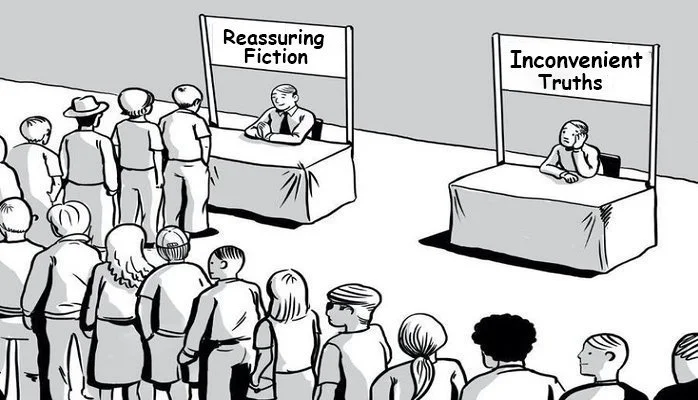

As the saying goes ‘never let the truth get in the way of a good story’. But it truly is quite remarkable how readily we will override our capacity for critical thinking in the face of a story we want to hear. As we will see, if the message on offer appeals enough to a particular desire or bias, it appears we will happily overlook whatever shortcomings in methodology and inconvenient flaws in logic are apparent. In this way, we can be active participants in ‘group think’.

We might then question our roles in upholding the conventions that abound in performance sport. Upon closer inspection, there is rarely logic in convention. It is beguilingly easy to fall prey to participating in such group delusion. On some level, we could argue that we willingly enter into this to prop up a particular tenet of our belief system in relation to theory and practice.

There is a strange insistence that participation and performance are entirely distinct and never the twain shall meet. But is there really no common ground to be found here? I will argue that participation and performance are NOT in fact mutually exclusive - especially in the case of youth sport. There is in fact plenty of overlap. So why should we keep them apart? Is it possible that bringing participation and performance back under the same roof might provide benefits in both directions?

A provocative title, so allow me to specify at the outset what exactly I am highlighting and the limits of the argument. Firstly and most importantly, let me make it clear that I am excluding from the discussion the necessary and vitally important domain of child-protection and the protection of vulnerable adults under law. What I am specifically referring to is the concept creep that has seen the safeguarding approach extended to sportsmen and women at senior level, who are otherwise (in the eyes of the law) deemed responsible adults capable of providing informed consent, making decisions and advocating on their own behalf. I am also excluding clear cases of misconduct that unamibiguously violate professional ethics and the boundaries of the athlete-coach relationship - for instance, sexually inappropriate behaviour or physical abuse. What I am also highlighting is the mission creep of those charged with investigating such claims and the present danger of over-reach. Why I feel these trends need to be challenged is that the safeguarding system if left unchecked threatens to penalise coaches simply for carrying out their proper duties.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

To celebrate the imminent release of the new title ‘Sports Parenting: Negotiating the Challenges of the Youth Sports Journey to Help Kids Thrive’ we are sharing this special post. The excerpt featured is from the chapter ‘Choosing the Right Programme’.

Environment is everything when it comes to developing talent. Parents are naturally highly motivated to find the programme that provides most optimal conditions to allow their child’s talents to flourish. Seeing past the sales pitch and making the right choice is however not a straightforward proposition. Being successful on this endeavour begins with understanding the key features that make for the most conducive setting to enable young performers to realise their athletic potential. In this chapter we aim to provide parents with some criteria to guide the search.

The inclination to question is not common - looking back, most of us would admit that we uncritically accepted what we were taught. There is a general assumption that authority figures know what they are doing, so it may not necessarily occur to us that the consensus view that is espoused might be flawed or even untrue. Yet it is always worth allowing for the possibility that the prevailing view may not necessarily have a sound basis or at least might be missing something important. It might serve us well to consciously foster in ourselves and others a readiness to challenge preconceived ideas and the received wisdom, simply in the interests of our own enlightenment. More broadly, it merits highlighting that willingness to question and to offer competing ideas are necessary ingredients for progress. Clearly this has some important implications for leaders and organisations, as well as for the professions and fields of study that we are part of.