Mentoring or apprenticeship is a universal path for developing coaches and practitioners across all disciplines. Indeed in many realms mentorship is often the primary means for practical learning, as well as passing on experiential knowledge. Given this, in the context of performance sport and related vocations it is notable that there are surprisingly few resources dedicated to this highly complex and multifaceted process. Even the rationale for mentoring seems incomplete. For instance, it is generally assumed what the apprentice or 'mentee' is getting out of the process; however, the motivation and apparent benefit to the person providing the mentoring is not typically considered. In this post we attempt to address this; we will tackle the why as well as the how of mentoring, and explore these aspects from the perspectives of both the mentor and the mentee.

HOW MENTORING SERVES THE MENTOR...

“@@Teaching is the highest form of understanding@@”

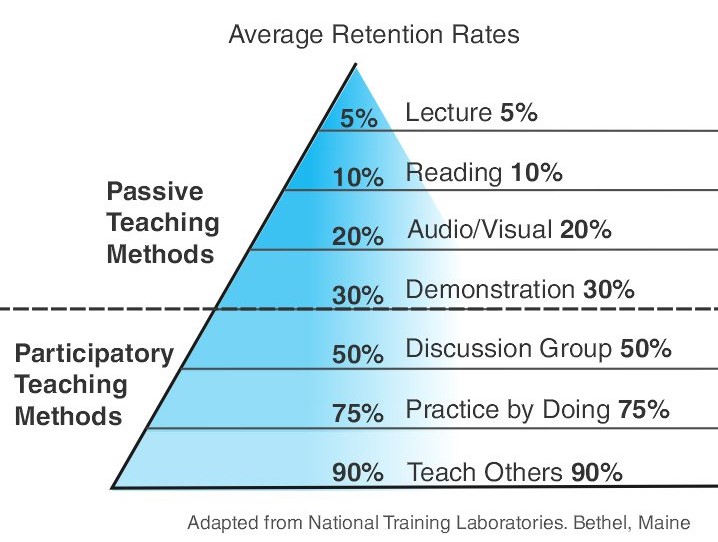

According to the pyramid construct of passive and active or participatory forms of learning, @@teaching (and mentoring) can be considered the highest form of 'participatory' learning@@. The level of retention with this method of active learning is rated as the highest of all. As such, @@the process of mentoring represents a means of continuing education for the mentor@@, just as it is for the one receiving mentoring.

Beyond learning and retention, organising one's thoughts in order to impart acquired knowledge, and the act of delivering this information, are processes that serve to deepen understanding. For instance, the question and answer part that follows will periodically throw up a question or perspective that the mentor has not considered before. Once again, this exemplifies how @@both mentor and mentee learn by engaging in the mentoring process@@.

Moreover, taking on the mantle of 'mentor' in itself encourages one to strive to invest the requisite time and effort to stay up to date. Mentoring inherently provides those concerned with the impetus to continue to broaden their knowledge, so as to remain equipped to deliver learning to those they are mentoring and answer their questions.

THE PROCESS...

As described in a previous post, the universal starting point when I engage in mentoring involves undertaking a SWOT analysis, whereby the learner evaluates their present strengths and weaknesses in designated areas, and identifies prospective opportunities, as well as potential threats or barriers.

Below are some examples of themes employed to guide the process of identifying signature strengths across relevant areas, as well as present 'weaknesses', or rather areas requiring development:

Theoretical knowledge/understanding

Technical expertise

Programming and prescription

Eye for movement

Instruction techniques

Interaction with athletes

This process provides a starting point for an initial discussion that serves to elucidate priority development areas. Generally, this is limited to two or three items, comprising topical areas of specific interest, and aspects where they identify a particular need to upskill. This process is revisited periodically in order to update and revise the personal development plan on an ongoing basis.

FILLING IN THE BLANKS..

Mentoring essentially bridges the gap between the learner's studies or training in the area and the applied knowledge required to become an effective practitioner in the field. In other words, the task of the mentor is to equip the aspiring practitioner with tools that are not customarily provided in the formal education process, and provide learning in areas not generally well catered for in lectures or textbooks.

@@Central to the mentoring process is translating 'book learning' and theory into a practical context@@. Often this involves a realisation that the textbook version of how things work differs to what is evident in practice. The role of the mentor is therefore to provide context and impart to the learner a true appreciation of applied knowledge in practice.

INTERNSHIPS...

Internships have become a mainstay of many professions in elite and professional sport, notably in coaching and physical preparation. As these 'opportunities' are often unpaid, or poorly paid, the main value offered to the intern is in the form of experience and practical learning. This practical learning typically occurs via a combination of mentoring, observation, and the experience of working alongside experienced practitioners with high-level athletes.

Despite the lack of financial compensation, competition for internship placement opportunities is often fierce; this is in part due to the saturation of the marketplace (a notable example is the field of strength and conditioning). Many aspiring practitioners face difficulties getting a foothold in the early part of their journey, and internships are increasingly considered a necessary part of the process of building a career in the 'industry'.

Sadly, the experiences offered to many interns do not meet their needs or expectations. With such a ready supply of free or cheap labour, some organisations abuse the internship process, and simply use interns for menial tasks and provide very little in the way of learning or mentoring in return.

Clearly, all internships were not created equal, so homework is required and it pays to be selective. Equally, if the aspiring practitioner chooses well and is successful in securing a place on reputable internship with people who are invested in the process, the experience can be invaluable and have a significant and lasting impact.

From a personal viewpoint, I regularly take on placement students and provide opportunities for graduates and other practitioners to spend time coaching on a voluntary basis; as part of the arrangement I personally provide individualised professional development and mentoring. I am particularly mindful of my obligations to the placement student or volunteer coach. In the absence of financial compensation it becomes more crucial to fulfil these obligations, by ensuring we provide equal or greater value in relation to time and effort they invest. Indeed I make it clear to the individual that in the event we ever fail to provide this value I fully expect and encourage them to walk away.

THE GIFT OF CURATING INFORMATION SOURCES...

In the Information Age, one of the biggest ways in a which a mentor can add value is by directing the young practitioner in their search for information. This is the virtue of information curation. Using their catalogue of information sources acquired over the period of a career, the mentor can direct their protege towards quality content on whatever topic they want to learn more about. This simple act can spare a great deal of time spent on fruitless searching, or worse becoming diverted by dubious material.

With the burgeoning resources and information sources available, what is needed is a highly developed filter; and this is the very thing that relative novices in the field lack. @@The ability to discriminate and differentiate quality information from a credible source is a critical skill@@. The mentor can help direct the search, provide a filter, and use the process to school their protege in critical thinking.

PREPARED...

It is important that novice coaches and practitioners are exposed to interacting with athletes early in the process. That said, throwing them in at the deep end is a high-risk strategy.

Operating in elite sport is not for the faint-hearted; from that viewpoint, an argument can be made that at some point there is a need to see if the individual will sink or swim. Nevertheless, putting a 'green' practitioner into a situation they are not adequately prepared for should be avoided where possible, unless done so intentionally (and with the consent of all parties) to serve a defined purpose or learning outcome.

Failing is to some degree an integral part of the learning process. Equally, putting a relative novice into a situation where they are essentially doomed to failure is basically an act of neglect, and is certainly not conducive to building trust in the relationship moving forward.

FINDING THEIR VOICE...

An essential part of the mentoring process is encouraging the young practitioner to find their own voice, and evolve their own style of coaching. Whilst they might adopt certain traits or behaviours they have observed from others, it is critical that the protege does not try to copy their mentor or emulate their manner of coaching.

@@In order to be credible a coach or practitioner must find their own authentic style@@. Regardless of the discipline or field of practice, the elements of 'coaching' and human interaction are integral to being an effective practitioner in sport. If the individual comes across as false or inauthentic they will fail to earn the respect or trust of the athlete.

@@AUTONOMY NOT AUTOMATONS@@...

Returning briefly to the topic of internships, an issue with institute of sport systems in particular is the tendency to seek to indoctrinate and mould interns in their own image. No system or organisation has a monopoly on best practice; and it is clearly a fallacy that any one approach is inherently superior. Indeed, seeking to institutionalise in this way is contrary to creating an environment for sustaining best practice and innovation. In that sense, @@any system that strives to create clones from those entering the organisation is doomed@@.

Conversely, @@the traits of inquisitiveness and free thinking should be highly prized and rewarded@@. As stated in a previous post, organisations that aspire to be elite should not hire applicants who parrot the most acceptable answers, but rather those who ask the best questions. This message should be emphasised and reinforced throughout the mentoring process.

“@@Great leaders do not create more followers; they create more leaders@@”

LETTING GO...

Even for those with a great deal of knowledge to impart, the hardest part of the process often comes in the latter stages of the relationship when the role of the mentee transitions from that of apprentice to becoming more autonomous. From the mentor's viewpoint this requires the ability and readiness to relinquish control when the time comes.

Practically, the preparations for this transition should occur at a much earlier stage in the process, by progressively giving freer rein and greater responsibility to the individual undergoing mentoring.

“@@Leaders become great not because of their power but because of their ability to empower others@@”

MENTORING EXPERIENCED PRACTITIONERS...

For the most part, so far we have discussed mentoring in relation to practitioners who are in the early stages of their career. However, mentoring is not only for novice practitioners; the benefits of having a mentor are apparent even for coaches and practitioners with many years of experience.

An indicative example is the 'Apprentice Coach Program' provided by Altis, a 'working' track and field training facility that provides education for coaches and practitioners. I have shared some reflections on the experience of a visit to Altis in a previous post. One notable point about this initiative is the use of the word 'apprentice' in the title, despite the fact that the majority of the coaches and practitioners who attend are highly experienced and well established. This underlines that even experienced and established practitioners recognise the value of apprenticeship (more's the pity it only lasts a week).

Clearly it is critical that the wealth of experience and knowledge that an experienced coach or practitioner brings with them is acknowledged in the mentoring relationship. Most often those who wish to engage in mentoring are seeking to learn from a mentor who has specific expertise in a particular area. In other cases, what the mentor provides is simply an alternative perspective.

The mentoring arrangement with an experienced coach is therefore far more akin to peer learning, as opposed to a hierarchical relationship. The mentoring process in such instances calls for humility on both sides.

“Dan Pfaff on the topic of ego in coaching: ‘If you are capable of honesty, and you have spent time in the trenches, sport is humbling every day (and ego isn’t an issue)’”

On a personal note, I am privileged to have served in such a capacity on occasion with Coach Paul Jackson of Ole Miss Rebels Football fame. I greatly respect Coach Jackson's knowledge and experience, and I think it is great credit to Paul that a professional of his standing is prepared to seek counsel and advice. In the instances Paul has come to me with questions I have simply shared some thoughts and proposed ideas for his consideration. It was therefore a surprise and a great honour when Paul recently referred to me as a mentor.

Enjoyed the read? For more on a variety of topics relating to athletic development, physical preparation and sports injury see the Books section of the website.